The Fourth Generation Warfare is characterized by a return to decentralized forms of warfare, blurring of the lines between war and politics, combatants and civilians due to nation states‘ loss of their near- monopoly on combat forces, returning to modes of conflict common in pre-modern times.

The Present Situation

We must reconcile with how the world has changed since the Cold War. Water flows in the direction where it finds the least resistance. The same is true about relationships – individual and collective, hence the new world alignments in which the United States, the European Union countries, Japan, and India are lined up against an assertive China. We should not, however, compare the post-Cold War alignments with the rivalry between the United States and the erstwhile Soviet Union. The world is no longer divided into two camps based on opposing ideologies. Ideological states have been replaced by “identity states”. It is not a matter of fight till death for either of the contestants. In many areas, the United States and China complement each other. While China blows hot and cold in the Pacific, it is very careful about overplaying its hand. In this new post-Cold War alignment, the United States, and the informal coalition it is trying to forge, view themselves as representatives of pluralistic and benign societies arrayed against an authoritarian and repressive China. For the last many decades, there are insurgencies and separatist movements going on in the Indian-held Kashmir and in its northeastern states. However, the western powers only focus on China’s restive provinces, especially Tibet.

Whereas China and India have a territorial dispute, this is not stopping them from cooperating with each other in the economic field. As a matter of fact, the Sino- Indian border dispute has become irrelevant for both the countries. They are living with it, and will continue to do so in the future. This brings us to the question: should Pakistan keep seeking symmetry with India by borrowing power from China? The answer is, clichés apart, there is no such thing as “all-weather friendship”. Pakistan’s Cold War relationship with China was based on the ground realities of that era. It derived its strength from the Sino-Indian border conflict. Since then, China has repaired its relations with India to a large extent. It has also come out of its world isolation and no longer requires Pakistan as a window to the world, as it did half a century ago. However, China still remotely needs Pakistan to checkmate India even as India needs Vietnam to checkmate China.

The India-centric aspect of Sino- Pak relationship, though not ceased altogether, has diminished to a considerable extent. However, the relationship has greater scope for expansion in another dimension. China needs Pakistan for an access to the Gulf oil fields and the Middle East markets. The so-called economic corridor linking China’s backward western regions with the Gwadar port is a step in this direction. The project provides Pakistan an opportunity to modernize its infrastructure, industrialize itself, and become a self-reliant nation. However, the manner in which the Pakistani politicians (including those in the government) are drooling over getting a share in the USD 46 billion bounty may dampen China’s enthusiasm.

INDIRECT APPROACH

Moving forward from the Cold War period, India-Pakistan rivalry has shifted to a lower dimension where proxy operations against each other have replaced conventional warfare. In this scenario, nuclear deterrence acts as a stabilizer which prevents the events from getting escalated beyond a certain level. After the 71 War, and particularly after the 1998 nuclear tests by India and Pakistan, a pattern can be discerned where both India and Pakistan have resorted to indirect approach to address their mutual differences. We notice manifestations of this approach in the Indian support of various separatist forces in Baluchistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Sindh, and its infiltration of religious extremists in Punjab. Many Taliban groups are also on the pay roll of Indian intelligence agencies. Pakistan is supporting the insurgency in IHK by maintaining that it is a freedom movement. It is logical for Pakistan, a weaker power, to resort to an indirect approach for the achievement of its strategic goal: recovery and integration of IHK with Pakistan.

What were the Indian motives to adopt an indirect approach for destabilizing Pakistan? We have discussed earlier how cautious and risk-averse Indian civil and military leadership is when it comes to settling scores on the battlefield. India attacked and absorbed small states like Hyderabad, Junagarh, Goa, and Sikkim, etc., because militarily they were no match for India. In 1962, Nehru tried to test the waters by provoking China through his forward policy. After India’s defeat, China declared a unilateral (and well thought out) ceasefire, restricting India from ever approaching within twenty kilometers of the Line of Actual Control and, to this day, India obliges China. In 1971, India attacked East Pakistan only when it was absolutely sure of its victory, but the Indian Army stopped in its tracks in the western theatre because of the human and material risks involved. In the future, India will resort to armed intervention in Pakistan only when it is absolutely sure that it’s offensive will be a walkover. Covert Indian intervention in Pakistan should be viewed in this context.

Seasons of Indo-Pakistan Confrontation

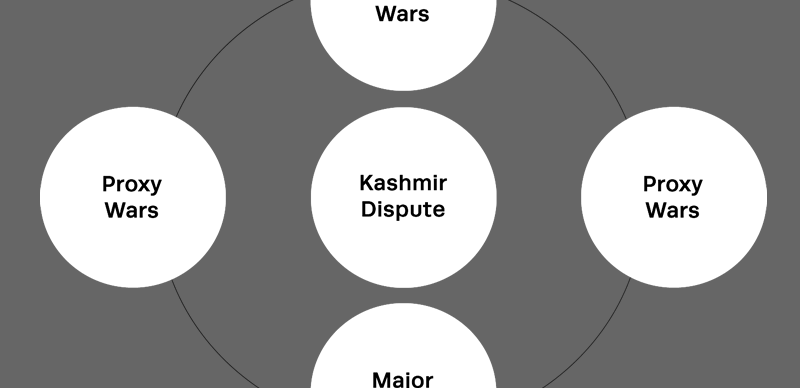

Not that indirect approach is a new phenomenon in South Asia. In the past, the intervening periods between conventional wars in the Subcontinent were peppered with proxy wars. However, after 1971, these have become the sole instrument of conflict resolution. If we liken the Kashmir dispute to the eye of the storm, Indo-Pakistan confrontation is like a weather system which has, over the last six decades, generated a seasonal cycle characterized by 1) major wars (47- 48,65, and 71); 2) lesser wars (Siachen-85 and Kargil-96); and 3) proxy wars. Presently we are living in the season of proxy wars. This completes the first cycle of the seasons of confrontation. Apparently, within the cycle, the seasons proceed in a linear fashion: major wars- proxy wars- lesser wars. However, it is more complex than we think. There are sub-seasons in a season.

The First Kashmir War, if we still count it among the category of major wars, in spite of its limited scope and restricted employment of the Pakistan Army, spawned the other two major wars in

1965 and 1971. As we look back, we find that during the period 1948-1965, both India and Pakistan, deriving motivation from their differences over Jammu & Kashmir, had been trying to destabilize each other through proxy wars. India, in cahoots with the Soviet Union and Afghanistan, supported the Pakhtunistan stunt as a result of which Afghan forces invaded Bajaur and Dir areas. Pakistan had to use its air force to get the Afghan aggression vacated. The first post- independence insurgency in Baluchistan, led by Sher Muhammad Marri, also had the Soviet and Indian Support. It was also during the 1948-65 period, when India started supporting the separatists in Sindh (Jiye Sindh) and East Pakistan (Awami League). It is an academic discussion if Pakistan reacted to the Indian moves or it was vice versa. However, during the same period Pakistan was also supporting the Naga and Mizo insurgencies in India’s northeast. Surprisingly, during this period Pakistan remained relatively inert in its support to the Kashmiris and, short of lip service, did nothing much to foment a rigorous uprising in the Valley.

The 1962 Sino-Indian border war indirectly influenced the Indo- Pakistan hostility matrix and led to the 1965 War. It was due to incorrect conclusions drawn from this border war, which made Ayub Khan and Bhutto believe that the time was ripe for launching an operation in the Valley. Pakistan tried to spark up an insurgency in IHK during a brief period between the Rann of Kutch conflict and launching of Operation Gibraltar and failed because of the short incubation period and lack of preparation.

During the period between 1965 and 1971 wars, both the countries kept themselves busy in propping up their respective proxies. Moreover, the Indians embarked upon a comprehensive plan to dismember Pakistan through the Soviet borrowed power. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan augmented Indo-Pakistan confrontation, even as the Sino-Indian war had earlier influenced the Indo-Pakistan rivalry. A significant addition, during this period, was the Khalistan insurgency, which was supported by Pakistan to interdict India’s line of communications to Jammu & Kashmir. Unable to do anything significant to neutralize Pakistan’s direction and control of the Afghan War, and while the Pakistan Army’s attention was focused on the western border, India exploited the gap between the northernmost point of the Line of Control and Pakistan’s border with China in the Trans- Karakoram Tract, and occupied the Siachen glacier.

After the 1971 War, Pakistan’s support to Mizo and Naga rebels had become irrelevant. Sheikh Muhammad Abdullah had grudgingly accepted Indian suzerainty and become chief minister of Indian-occupied Jammu & Kashmir. However, a decade later (in 1981) Sheikh Abdullah was terminally ill and Pakistan had decided to exploit the vacuum that was going to be created after his death. Moreover, Kashmiris were fed up with the corruption rampant in IHK under Abdullah’s rule. Conditions for a fresh uprising were thus being created in the Valley. It has been stated that Pakistan’s support to the Kashmiri separatists is not in retaliation to what India is covertly and overtly doing to destabilize Pakistan, it is because Pakistan considers the uprising in Jammu & Kashmir as a genuine liberation movement launched by its people.

The one significant movement abetted by Pakistan in retaliation to the Indian subversive operations was the Khalistan movement. In 1980 or thereabouts, nuclear deterrence had established itself in the Sub-Continent and, while the Indian leadership bristled due to Pakistan’s support to the Khalistanis, the 1986 standoff between India and Pakistan remained inconclusive.

Contrary to the general perception, Khalistan movement was not started by Zia-ul Haq. According to Raman (2012) a retired officer of RAW:

“ …. In 1971, one saw the beginning of a joint covert operation by the U.S. intelligence community and Pakistan’s ISI to create difficulties for India in (Indian, sic) Punjab…. The U.S. interest in Punjab militancy continued for a little more than a decade and tapered off after the assassination of Indira Gandhi.

After assuming power, Zia resumed (or intensified) Pakistan’s support of the Khalistan movement by starting, what the Indians call “Operation Topac”. This operation dovetailed operations in J&K with the Sikh insurgency. Perhaps Pakistani leadership was never serious about the Khalistan movement beyond the consideration that a restive Indian Punjab disrupted Indian Army’s line of communications to the Indian-held Kashmir. The Khalistan insurgency was not started by Zia. It was resurrected during the 1980s in retaliation to Indira’s ham- handed policies against the Sikh community. Zia exploited the Sikh turbulence in East Punjab. The undeclared nuclear deterrence in the Sub-continent (Pakistan had not yet shown its hand) had transformed India-Pakistan hostility into a slow burning and long drawn out war which continues to bleed both the countries. India and Pakistan, though both of them deny it, are using terrorism as an instrument of state policy. Being a weaker power will not make Pakistan blink even as being weak has not deterred Vietnam and Taiwan from defying China. Such are the dynamics of power. Paradoxically, Pakistan’s present political instability makes it a more credible nuclear weapons state than India.

Kargil, according to Vajpay, was a “near war”. We categorize it, like the Indian operation in Siachen, as a lesser war. Thereafter, the Subcontinent was plunged into a grand season of proxy wars such as the terrorist war waged in Pakistan by the Taliban, and the Indian sponsored civil war in Karachi, interior Sindh, FATA, and Baluchistan. Indians accuse Pakistani proxies of launching terrorist attacks on the Indian parliament and in Mumbai. We have to take the Indian accusations seriously. The season of proxy wars will not last forever. It will end somewhere. However, once the proxy wars come to an end, and the seasonal cycle is completed, it should logically start all over again with the season of major wars under a nuclear overhang. Both the sides are honing their respective doctrines to fight such a war. All the while, Jammu & Kashmir remains in the eyes of the storm. It is easy to say that Pakistan should peacefully resolve its territorial differences with India. It needs two to tango. One time or another, one side refuses to dance. Maybe in the 22nd Century there is peace between the two countries. Till then both these countries, it is feared, will learn the things the hard way.

The writer is a retired Army officer. Writes on issues related to national and International affairs, important events from military history, and military technology. Considers writing as an instrument to calibrate his mind.